With 2020 finally over (good riddance) now is the traditional time for an annual performance review, and who am I to argue with tradition?

In this review I will:

- measure my portfolio’s short, medium and long-term performance against an appropriate benchmark and

- think about what went right and what went wrong, and how that knowledge can be used to improve future performance

Table of Contents

- Investment goals

- Total returns: Negative in 2020, but ahead of the market over ten years

- Dividends: Yield in line with the All-Share, dividend growth picture is more complicated

- Volatility and risk: Bigger declines than the All-Share during the crash

- Positioning the UK Value Investor portfolio for 2021 and beyond

- Selling the lowest quality, least defensive and worst value holdings

- Selling Aggreko: A high quality business operating in markets with extremely large, long and hard to predict cycles

- Selling Ted Baker: A low quality cyclical fashion retailer with too much debt

- Selling Xaar: An extremely cyclical business pushing too hard for growth

- Selling Dunelm: A high quality retailer trading at a potentially lofty valuation

- Buying high quality defensives and high quality cyclicals at attractive valuations

- The long road to £1 million and beyond

Investment goals

Before I dig into my results for 2020, here’s a brief summary of what I’m trying to achieve with the UK Value Investor portfolio:

High yield: It’s a UK-focused income and growth portfolio, so it should have a dividend yield at least as high as the FTSE All-Share (or more specifically, a FTSE All-Share tracker fund).

High growth: The portfolio’s dividend should grow faster than inflation and faster than the All-Share’s dividend. In turn, dividend growth should drive capital gains, so the portfolio’s total return (dividend income plus capital gains) should exceed the FTSE All-Share’s total return over the long-term.

Double digit returns: Ideally, total annualised returns should exceed 10% over the long-term as I think this is achievable. This is also the rate of return required for the portfolio to hit its target of reaching £1 million by 2041.

Low risk: The portfolio should be less volatile than the All-Share, with smaller declines in bear markets.

To achieve those goals I follow a defensive value investing strategy. In other words, I invest mostly in FTSE 100 and FTSE 250 companies with attractive dividend yields and long track records of consistent dividend payments and dividend growth.

So that’s what I’m trying to achieve, and this is how things worked out in 2020:

Total returns: Negative in 2020, but ahead of the market over ten years

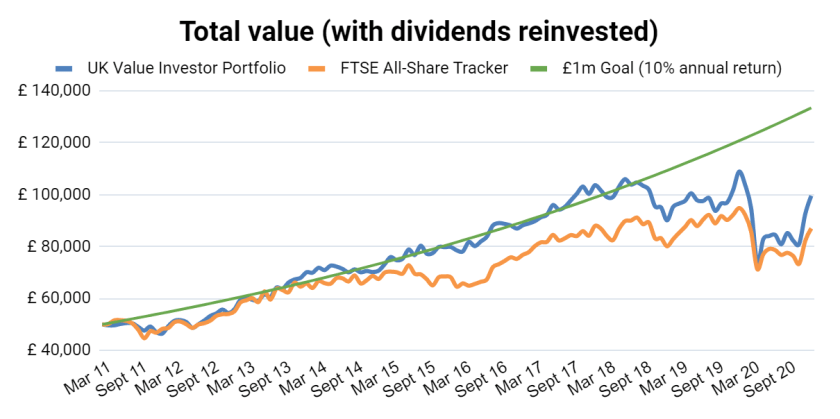

The FTSE All-Share fell 8.3% in 2020, including reinvested dividends, while the UKVI portfolio fell by 8.6%. So overall the portfolio was very slightly behind its benchmark over the short-term.

As all experienced investors know, results in any one year are almost always meaningless, so here are the results for the portfolio and its All-Share benchmark over ten years:

Long-term investors should focus on the longer-term, and for me that means five-years at least and preferably ten-years.

Over those time frames the portfolio is fractionally behind the All-Share over five years and slightly ahead over ten years. However, in both cases the differences are quite small, so I would describe the portfolio’s results so far as being broadly in line with the UK market.

That isn’t good enough, so I’ll reiterate the all-important total return goal:

- Goal for 2021: Drive total annualised long-term returns back above 10%

Dividends: Yield in line with the All-Share, dividend growth picture is more complicated

2020 was not a great year for dividend investors. The All-Share’s total dividend for 2020 fell by 33% compared to 2019 while the UKVI portfolio’s dividend fell 36%.

The fact that the portfolio’s total dividend for the year fell more than the All-Share’s is disappointing, even though the difference was very small. So here’s another goal:

- Goal for 2021: Improve the robustness of the portfolio’s dividend

As annoying as they are, I expect these dividend declines to be relatively short-lived. In fact, many of the portfolio’s holdings have already reinstated suspended dividends, although some have taken the opportunity to rebase them to a lower level to fuel future growth.

Turning to dividend yield, at year-end it was 2.9% for both the UKVI portfolio and its All-Share benchmark.

Historically the portfolio has had a consistent yield advantage over the All-Share, so hopefully the portfolio’s yield can revert back to its typical 4% range within a year or so.

- Goal for 2021: Drive dividend yield back above the All-Share’s and preferably above 4%

As for long-term dividend growth, this is easy to measure but harder to draw conclusions from.

If we ignore 2020’s abnormally low dividends as an outlier, then the portfolio’s dividend has grown more slowly than the All-Share’s over the last ten years (6% annualised versus 9%).

This slower dividend growth is mostly because the portfolio has moved towards higher quality stocks with slightly lower yields over the last ten years.

In other words, a decade ago the portfolio was mostly invested in lower quality lower growth stocks with yields of more than 5%, whereas just before the pandemic the average yield was 4% from higher quality higher growth companies.

In short, the decrease in yield has acted as a drag on dividend growth.

Going forwards I don’t expect the average yield to continue dropping, so I expect the higher dividend growth rate from the portfolio’s higher quality holdings to show up as higher overall dividend growth over the next few years.

Here’s the related goal:

- Goal for 2021: Grow the portfolio’s dividend faster than the All-Share’s

Volatility and risk: Bigger declines than the All-Share during the crash

2020 broke records for the fastest stock market crash in history. The All-Share fell 34% in four weeks from late February to late March, while the UKVI portfolio fell 40% over the same period.

Given that the portfolio is supposed to be defensive, that’s far from ideal. However, again, the degree of underperformance wasn’t huge, but it was disappointing and needs fixing:

- Goal for 2021: Improve the defensiveness of the portfolio so it declines less than the All-Share in down years

The market and the UKVI portfolio have since recovered almost all of that lost ground and the lows of March, April and May turned out, as I suspected, to be excellent buying opportunities.

Positioning the UK Value Investor portfolio for 2021 and beyond

Although the portfolio’s results haven’t been terrible and it has outperformed the market (slightly) over ten years, it’s disappointing to be some way off the 10% sustainable annualised return I’d hoped for.

Let’s take another look at my goals for 2021 (and beyond):

- Drive total annualised long-term returns back above 10%

- Improve the robustness of the portfolio’s dividend

- Drive dividend yield back above the All-Share’s and preferably above 4%

- Grow the portfolio’s dividend faster than the All-Share’s

I think all of these goals can be achieved with two fairly minor tweaks to my investment strategy.

Essentially, a recent review of all my past and present investments revealed that the best performers tended to be the highest quality, most defensive, best value holdings, while the worst performers tended to be the lowest quality, least defensive, worst value holdings.

My dazzling insight is that the portfolio needs to be tilted towards its highest quality, most defensive and best value holdings, and away from (or out of) its lowest quality, least defensive and worst value holdings.

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about this in recent weeks and have already detailed how I intend to do this in two blog posts:

- How to categorise stocks as quality, defensive and/or value

- How to build a concentrated portfolio of quality shares

In practical terms, this will have several important effects on the portfolio:

- The number of holdings will reduce from 34 today to around 20 to 25 by the end of the year as the weakest holdings are removed

- The maximum position size will increase from 6% to 8% (if a position exceeds 8% I’ll trim it back) to allow a greater focus on the best holdings

- A new minimum position size of 2% will be introduced so that all holdings pull their weight (and if I’m not confident enough to top up a sub-2% position then I’ll sell it)

- The position size of each holding will approximately reflect the confidence I have in the stock’s ability to exceed my 10% annualised return target. So:

- High confidence holdings will have overweight positions of around 5% or more

- Average confidence holdings will have average-weight positions of around 3% to 5%

- Low confidence holdings will be sold or have underweight positions of around 3% or less

The idea is that this tilt towards the highest quality, most defensive, best value stocks will improve the portfolio’s dividend yield, improve its dividend and capital growth rates and improve its defensiveness.

This process of rebalancing the portfolio towards its best holdings has already begun. At the beginning of January I trimmed an oversized Quality Value holding and used the proceeds to top up an undersized Quality Defensive Value holding.

The Quality Defensive Value holding has a higher yield, a higher growth rate and a more defensive business model, so hopefully this will improve the portfolio’s results in 2021 and beyond.

I expect many more rebalancing trades to occur in 2021, and in a relatively short time the highest quality, most defensive, best value stocks (those in which I have the most confidence) will dominate the portfolio.

And speaking of trades, here’s a quick review of every company that joined or left the portfolio in 2020.

Selling the lowest quality, least defensive and worst value holdings

In line with my growing focus on Quality Defensive Value stocks, four companies left the portfolio in 2020. All of them were either low quality, highly cyclical or unattractively valued, and in some cases all three.

Selling Aggreko: A high quality business operating in markets with extremely large, long and hard to predict cycles

Aggreko is the world leader in portable containerised diesel generators, which are used to power events such as the Olympics or to build temporary or off-grid power stations.

Having invested in 2016, I sold Aggreko in January 2020 for a measly 2.5% annualised return.

This investment’s weak returns are due to the fact that I failed to realise just how cyclical Aggreko really was, and how much it had benefitted from potentially one-off cyclical tailwinds in the years leading up to my purchase.

Those tailwinds eventually turned into headwinds and the company ended up struggling against them for years.

This degree of cyclicality makes it incredibly difficult to form sensible opinions about Aggreko’s future revenues, earnings and dividends, and I now think that such a cyclical company isn’t a suitable holding for the UKVI portfolio.

Selling Ted Baker: A low quality cyclical fashion retailer with too much debt

Ted Baker is a relatively well known high street fashion brand and retailer which joined the portfolio in late 2018.

Ted ran into a series of very serious problems which showed that the company was fundamentally weak, so I sold Ted Baker in July. The sale locked in a loss of almost 94%, which was about 4% of the portfolio’s overall value.

Ted’s problems stemmed from a combination of weak returns on capital and excessive growth. This only becomes obvious once returns on capital employed are adjusted to take account of lease liabilities, which is something I didn’t do in 2018.

Ted’s weak returns gave it little cash to reinvest for growth, so it chose to use external funding instead.

The end result was excessive lease costs and too much debt. When demand for high street fashion turned downward in 2018, the company’s lack of competitive strength (the underlying cause of its weak returns) and weak financial foundations led to a host of extremely serious problems.

On a more positive note, Ted provided many lessons on what to look for if you want to avoid weak over-indebted retailers:

- Why Ted Baker has been a disaster and a gift in equal measure

- Ted Baker’s collapse is a lesson in the dangers of too much growth

Selling Xaar: An extremely cyclical business pushing too hard for growth

In September I sold Xaar, a leading high tech digital inkjet printhead business.

Xaar has the potential to be a quality business, but it’s also extremely cyclical. Demand for its revolutionary digital inkjet printheads can explode in an industry where everyone still uses analogue printing, but then collapse once the industry has fully converted to inkjet.

Xaar has also consistently struggled to hang onto market share in newly converted markets once serious competition arrives.

Extreme cyclicality should demand caution so that the business can survive when demand temporarily collapses. But Xaar chose to invest very heavily in ground breaking new technology even as revenues shrank, and it over-committed.

By 2019 Xaar was near bankruptcy and I had learned some very important lessons about why very cyclical businesses shouldn’t be in a defensive value portfolio.

Selling Dunelm: A high quality retailer trading at a potentially lofty valuation

Most of the sales I made in 2020 could be described as taking out the trash. In contrast, the year ended on a more positive note with the sale of Dunelm in November.

Unlike Aggreko, Ted Baker and Xaar, Dunelm is exactly the sort of company I’d like to keep in the portfolio.

It’s the market leader in UK homewares, it’s highly profitable, has a strong balance sheet and still has a member of the founding family on the board.

Founding family ownership and involvement can be useful as it often helps management stay focused on the long-term future of the business rather than meeting the short-term profit expectations of institutional investors.

We give each [of Berkshire Hathaway’s managers] a simple mission: Just run your business as if (1) you own 100% of it, (2) it is the only asset in the world that you and your family have or will ever have; and (3) you can’t sell or merge it for at least a century.”

Warren Buffett

The investment in Dunelm produced a 15.8% annualised return over four years and I would gladly reinvest in the company if its dividend yield gets back above 4%.

Buying high quality defensives and high quality cyclicals at attractive valuations

With share prices depressed through most of the year I took the opportunity to add eight companies to the portfolio. All of these companies were high quality and attractively valued according to my Quality Defensive Value criteria.

To give you an idea of what I’m now looking for in an investment, here’s a snapshot of some key metrics for these eight new holdings:

For me the most important metric is ten-year net return on lease-adjusted capital employed (net ROCE), which is usually a good measure of a company’s sustainable competitive strength.

All eight of these companies produced above average net returns on capital over the last ten years and, as a group, their average net ROCE of 25% is more than double the market’s average of about 10%.

Also, six out of eight of these companies are in either the FTSE 100 or FTSE 250, in line with my policy of investing mostly in medium or large-cap UK stocks.

The long road to £1 million and beyond

My long-term goal is for the portfolio to reach £1 million before the end of 2041.

That requires a 10% annualised rate of return over the 30 years from the portfolio’s 2011 inception date, and until mid-2018 the portfolio was eerily close to that target growth rate.

My job now is to get the portfolio back on track to hit its £1 million long-term goal, whilst also maintaining a market-beating dividend yield.

In recent months the dramatic post-crash recovery has massively reduced the gap between where the portfolio is and where it needs to be to hit that £1 million target.

Even so, it might take a few years to get back on track. But I’m confident it can be done.

Very brave analysis and brilliant teaching. I am now holding Aggreko, Xaar and Ted Baker. All bought in the last third of 2020!! Reasons: Batteries/Biden, New Tech Cycle and renegotiated leases/Next platform. But your appraach has many lessons for me. Thank You.

One thing to remember. In March: IT’s. I bought a tiny amount of JP Morgan Smaller Co’s, I rose 103% by end Dec. When everyone thiks the s*** has hit the fan buy good IT’s.

Hi Neal

For every seller there is a buyer! I think Aggreko, Xaar and Ted Baker can be fine investments for the right sort of investor at the right price, e.g. someone interested in deep value and turnarounds during March.

In Xaar’s case it’s almost a ten-bagger since March, so I’m sure somebody’s made a ton of money out of that one.

But in my case they’re not what I’m looking for, so post-sale price rises are irrelevant (but still very annoying!)

John, thank you for sharing your annual retrospective, again. I appreciate that you reveal your most painful trades to your readers and analyse them to learn lessons and evolve your strategy.

The tilt toward ROCE caught my eye because it is emphasised in Terry Smith’s book (https://www.harriman-house.com/investingforgrowth) as a measure of quality.

It is inspiring how you are willing to adapt your strategy. I wish you good luck finding quality companies with sustainable dividend yield of 4%. This is hopefully a good year since the UK has been shunned by international investors for 4 years.

PS: it would be helpful if your article had a footnote about the inclusion/exclusion of transaction costs, bid/ask slippage, stamp duty, etc. The index tracker performance presumably includes all these costs so it would not be fair to compare it to a model portfolio which assumes that transactions occur at the market closing price.

PPS: over the holiday season I contacted the companies that hold my SIPP and ISA to investigate these costs. I learned that their service is RSP rather than DMA so I am now looking for the latter. When I purchase shares for £10,000 the round-trip cost is around £250 (or more), which is 2.5%. If I hold for 2.5 years, on average, that is a 1% drag on the performance of the portfolio, thus 8.6% excluding costs is 7.6% net.

Hi Ken

Regarding your PS I’ve added a little notice box near the top of the article which says:

“The UKVI portfolio holds exactly the same stocks as my real-world portfolio. It deducts the cost of broker fees (£10 per trade), stamp duty (0.5% per purchase) and an annual subscription to the monthly UK Value Investor newsletter. Buy and sell trades are recorded at the actual trade price from my real-world portfolio.”

In other words, the portfolio’s results should be identical to a real-world portfolio making exactly the same trades. The only thing missing are platform fees, but some broker platforms are effectively free so I don’t think that’s an issue.

As for your PPS, it’s an interesting point and I haven’t really looked at the different routes to accessing the market. I guess that has something to do with the fact that I invest mostly in mid and large-cap stocks, and even my small caps typically have market caps of hundreds of millions of pounds. The bid-ask spread and associated drag is tiny for these companies.

Take S & U, my most illiquid holding. The bid-ask spread is about 1%. Add to that 0.5% stamp duty and 0.5% broker fees (2x£10 on a £4,000 trade) and the round trip cost is 2%. My typically holding period is about 5 years, so 0.5% per year.

However, most of my holdings have a bid-ask spread of less than 0.2%, so using the standard Retail Service Providers (market makers) isn’t much of an issue.

Having said that, it’s more of an issue for very illiquid shares or very large trades, so if you find a decent Direct Market Access platform then feel free to post a comment on it here.

Hi John

Thanks for the regular annual review. As has been discussed on your blogs in the past, although one year metrics aren’t meaningful in isolation and shouldn’t be used as evidence to buy or sell, I still think they are helpful to give an indication how the portfolio is performing compared to the market in general and to tweak the general approach, as you have done. If nothing else, it’s great emotional support to know after a tough year ‘we’re all in this together’!

My value portfolio had an equally poor year with overall loss of 10.60%. Mainly this is down to having too many cyclical businesses that all lost ground and the weaker ones dwindled away to the point they aren’t going to recover enough to justify keeping them in the portfolio (Mitie, John Menzies, Lookers). But later in the year I took the opportunity to invest in some more defensive, better quality stocks (Direct Line, Telecom Plus) which are already showing double digit gains, which eases the pain a little. Persimmon was my only long term holding that grew significantly (8.6%) which, as it’s by far my largest holding, was a bonus.

Here’s to a far better 2021!

Cheers

Steve

Hi Steve

2020 was a bit of a crapshoot. If you happened to own tech or pharma, or companies linked to those industries, then it was a great year. Or if you owned anything frothy and speculative then you probably would have seen huge gains thanks to the new army of lockdown traders!

But if you owned anything to do with aerospace or meeting people face to face (events, restaurants etc) then it was pain all the way down.

Either way, a lot of 2020 is down to luck, or a lack of it, so investors shouldn’t get too depressed or excited by this one very unusual year.

In terms of long-term results I don’t think 2020 did too much permanent damage to my portfolio. A couple of companies had to carry out emergency rights issues which diluted existing shareholders, but most of my holdings got away with temporarily suspending dividends and a handful actually benefitted from the pandemic, as unpleasant a thought as that is.

Let’s hope 2021, or at least the second half of 2021, is much better.

It’s very hard to substaintially beat the market when you have a fairly even spread across 30+ holdings you effectively become more and more of an index hugger, no matter what analysis you may be applying!

Hi Van,

That’s basically the conclusion I’ve come to this year. I’m now looking forward to being more selective, holding fewer but better stocks and adjusting position sizes based on my opinion of each holding.

Hi John,

This may interest you, in a recent study they found that something like 10% of the US Stock market return between 1926 to 2017 was generated by only a few stocks including: Exxon Mobile, IBM, GE, Altria, Dupont, Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Apple and Microsoft. I think this highlights the issue that most stocks generally fail to generate a decent return. They lack the competitive advantage to generate a high returns on minimal assets.

I think this suggests one thing if you want to beat the market then you have to concentrate but to concentrate successfully you really need to understand a sector in-depth warts and all. If you feel uncomfortable doing this then an index fund is probably the way to go but I think it needs to be a multi decade strategy because the S&P 500 is currently grossly overvalued and it wouldn’t be a stretch to assume that at current price it represents future returns. Hence it is overpriced and only over a multi decade time frame you will capture a decent return.

For me I’ve taken a concentrated approach as regrettably I only seem to understand a specific area and my disaster with AA always reminds me not to invest in businesses you don’t understand. Whilst I think even index funds can be a disaster the Japanese Index funds are a good example where the Japanese economy was too reliant on one sector and once it lost its competitive advantage in such industry returns have not materialised in the index fund. The S&P 500 is driven by FAANG stocks but if you look at the Chinese fintech eventually these companies may challenge US dominance and who knows what will happen to the S&P 500?

Hi Reg

I agree to an extent, although I don’t think you “have” to be super-concentrated. I think factor investing can work, but it probably works best if you own the whole market (i.e. hundreds of stocks) and weight the market based on the factors, and possibly go short stocks with poor factors.

This is the sort of thing that Joel Greenblatt (Magic Formula) has set up in the US and I think it can work as long as the factors don’t weaken over time as more investors (and quant hedge funds) use them.

But of course that’s not super practical for retail investors picking their own stocks, so yes, concentration probably makes more sense for normal humans.

Also, I think over huge periods it looks like a few companies make all the returns because most companies go bust or get taken over or leave the public market during that time. But over shorter periods of a decade or three many companies do produce extremely good returns for shareholders, so I don’t think you have to be ultra picky about the company or look for companies that can last centuries.

I think half of the need for concentration comes from the relatively small number of quality companies that are likely to survive and thrive over a decade or three (at least), and the other half of the need for concentration comes from the fact that most of the time very few of those quality companies are available at suitably attractive valuations.

For example, I’m currently working through my stock screen doing a quick sub 1hr review of each stock, and as Buffett’s experience suggests, there aren’t many quality companies with double digit expected returns. But I think there should be enough to fill a reasonably diverse portfolio of 15-20 companies (and more if you invest globally rather than just in the UK).

Hi John,

The good thing is I have a more international outlook because the ROCE/ROE levels I’m looking for limits the pool of stocks I can invest within the FTSE. The other thing I’m looking for is a substantial discount i.e. a stock with a PE of 40 down to PE 20. Situation like this does happen but more than often the market is right to downgrade a given company and the only way you can go against a market is if you happen to know the sector inside out. Otherwise most cases are a value trap. Unfortunately the decline in share price makes it irresistible to value investors and often they end up losing their capital.

One of my favourite examples is McDonalds in the late 90s it was cannibalising sales via over expansion and by 2002 reported its first loss. As a result McDonalds lost 70% of share price between 1997 to 2003. Unfortunately if you looked at the balance sheet to the uninitiated it would have looked like McDonalds had very poor prospects. On the other hand if you understood the fast food business you would understand how durable the company is and furthermore look at ROCE from earlier reports and be able identify the fact that over expansion has hurt the business but it could be remedied.

Unfortunately most buyers were shunning the stock because they lacked the insight to see what a wonderful opportunity it was. Interestingly Ray Kroc who founded the franchise was in the business of supplying cups and products to the fast food industry and in his book he attributes to his inside knowledge which enabled him to identify the business.

I think over a period I might be able to diversify but I have to balance it based on the number of opportunities I get in the stocks I am interested in.

“I have to balance [diversification] based on the number of opportunities I get in the stocks I am interested in”

Good point. I guess over the next year or so I’ll find out how many stocks there are in the UK market that fit my ever-increasing standards.

If I can only find say 15 super-attractive stocks then I’ll probably top that up to 20 or so with a few more quality holdings where the price is less attractive. These would be small positions where the expected returns is still acceptable (perhaps similar to the market’s average expected return) and the positions could be expanded if prices become more attractive.

Hi John,

Thank you very much for showing this and providing an excellent analysis of your fund over the last year.

One thing that I think limits your ability to get the 10% return over a calendar year on a consistent basis is that you focus solely on UK stocks. Although the UK market is undervalued by the Schiller ratio other great opportunities for 100 baggers are around in the international markets and businesses that have a consistent high returns on capital employed.

Another suggestion would be read the letters of Nick Sleep who advocates for a investment approach that is focused on selecting a concentrated portfolio of high quality companies that annually compound in value and growth. Nick Sleep had a portfolio that consisted of three stocks (Berkshire Hathaway, Costco, and Amazon) which consistently beat the market return.

Last suggestion is to use Dataroma hhttps://www.dataroma.com/m/home.php) for share idea creation when thinking about purchasing new stocks. They have a list of the stock holding of investors who consistory beat their benchmark of which only 3% do.

Hope some of the above help as you seek to get you portfolio back on track in hitting you annual 10% return target.

Best,

Amit

Hi Amit, thanks for the suggestions.

Investing outside the UK: This is something I may do in future, but for now I want to focus on the UK. The All-Share has over 600 companies, over 200 of which have paid unbroken dividends for at least ten years (although 2020 may reduce that number somewhat). So there’s a lot to chew on in the UK.

I’ll know within a year or two whether I can build a concentrated portfolio of quality stocks from the FTSE All-Share. If there just aren’t enough attractively valued quality companies then I’ll have to look abroad.

Nick Sleep: I’ve got a copy of the Nomad Investment Partnership letters, written by Nick Sleep, so I’ll be reading through them over the next few weeks. Should be interesting, but I don’t think I’m going to hold just 3 stocks anytime soon.

My thinking on position sizing is more like some of the examples here:

http://oxstones.com/position-sizing-in-value-investing/

My current plan is to boil the portfolio down to the best ~20 investments. The most attractive stocks will have positions sizes of say 6% to 8%, medium stocks will be 4% to 6% and lower conviction stocks (e.g. quality company but valuation less attractive, or quality company where the risk level has increased for some reason or other) will be 2% to 4%. Anything below 2% will be topped up or sold.

Dataroma: Thanks for the suggestion but I prefer to borrow fundamental principles from the best investors and try to apply them myself, rather than borrow specific stock ideas.

Hi Amit

thank you for those two references

I had not heard of either site

Plenty of interesting reading there

I also agree with you that while it may be possible for John to achieve his objective by focusing on UK stocks, it would be considerably easier if he incorporated US and other stocks – but of course that would be a major change in his mission and focus

Nicholas

Hi Nicholas,

Whether I end up looking outside the UK depends on what’s available in the UK. For now I’m focused on FTSE All-Share stocks, so my first job is to map out the investible universe there, which will take a while.

If there are enough good opportunities in the All-Share then I don’t see that the additional effort of adding in hundreds of other companies from the US or elsewhere is worth it.

But if the FTSE All-Share has too few quality companies or too few at attractive prices, then I might start looking at companies in the AIM 50 or AIM 100.

Given that I’m now looking to hold around 20-25 companies, hopefully the 600 or so in the All-Share plus another 100 from the AIM 100 should be a big enough pond to go fishing in.

“Although the UK market is undervalued by the Schiller ratio”

Amit

Schiller was an eighteenth century German poet and philosopher !!

And obviously way ahead of his time, if we are only now starting to note his investment wisdom.

But if we like stocks because of their volatility, to sow and duly harvest; then concur London listed stocks offer domestic and international opportunities aplenty, to augment our ventures into listings in other financial centres..

John,

Your long term results may be under the 10% target but they are still beating the index by a reasonable amount and I expect you took less risk to get there. So I think you’ve done very well.

My two cents: I believe you are correct that reducing the number of holdings will make it easier to outperform by larger amounts. I think bringing the number down to 10 to 15 and focussing on your strongest ideas would be even better.

I also think you will find eventually that adding to falling stocks is a mistake. The size of a position should be based on the risk of permanent loss. The higher that risk the smaller the bet should be. But, a stock’s risk of permanent loss rarely declines when the price falls. If anything it is a sign of increasing risk. So what is the case for adding money? If it’s ok to add to the fallen stock from a risk perspective then, logically speaking, you didn’t put enough in to start with!

Adding to losing stocks is admitting that your original position sizes are systematically too small and you are diluting your best ideas with excessive diversification. If the diversification is NOT excessive then there should be no room to add money to any of the positions since they were already maxed out from a risk perspective at the point of purchase.

I also think trimming winners is a mistake. I’m sure I’m in the minority here, but I believe that diversification should be based on cost not market value. A rising stock does not increase your risk overall. You could argue that higher concentration in a winning stock exposes you to a greater chance of a reversal. But it’s also true that you have more money to lose when a stock performs unusually well. It’s nice how that works!

The greater risk is cutting off big winners early. And history clearly shows that stock market returns are highly skewed. It’s almost impossible to have a strong long term record without any large winners. Even Ben Graham, probably the greatest advocate of making many small gains, earned more money from holding ONE stock (Geico) than he did from all the thousands of small trades his partnership made over decades combined.

As always, if you feel you have some ability to identify the odd misplaced bet in the stock market, why abandon that skill with automatic rebalancing rules? Surely you’d be farther ahead by using the same skill that got you into the right stocks at the right prices in the first place. And if you don’t feel you have that skill (I think you do) then why aren’t you in index funds?

As Charlie Munger would say: you’ll see it my way eventually because you’re smart and I’m right!

Hi Rod, thanks for such an insightful comment.

I started to write a reply but it became very long for a blog comment, so if you don’t mind I think it would be more useful to write the reply as a blog post because you make a lot of points that deserve a decent reply.

If you’re happy with that then I’d like to quote your comment in that blog post, which I’ll hopefully get written up next week.

Thanks again

John

Update 26/04/21: I was hoping to write a blog post reply in Jan/Feb, but it’s almost April and the post is still in draft form. Hopefully I’ll get round to it later this year as the topics are worth covering.

Excellent post

I have reached the same conclusions

Cutting your winners too early is almost always a mistake, as you rarely get an opportunity to reinvest, absent a market crash

the only reason to sell winners is if you have a better investment at a more attractive price

and I love the Charlie Munger quote!